Short summary of the Colonial Era of Rhode Island: 1636-1765

The colonial era for Rhode Island began when the Dutch explorer Adriaen Block who visited what became Block Island in 1614. His visit was part of his voyage of exploration of the New England coast. Block Island is an island off southern Rhode Island at the eastern entrance to Long Island Sound.

However, the date usually given for the founding of Rhode Island is 1636, when Roger Williams founded his town of Providence across the river from the westerly edge of the Plymouth Colony. Block Island was settled only on 1661, about 30 years later after Providence. The island only became a part of a recognized colony by the Charter of 1663, which recognized it as part of Rhode Island.

The Founding of Providence

Providence, was founded in 1636 as a settlement by English clergyman Roger Williams, after he was banished in 1635 by the Massachusetts Great and General Court. Williams selected the name in gratitude for “God’s merciful providence” that the Narragansett have granted him title to the site.

The land upon which Roger Williams planted his town of Providence was purchased by him from the Narragansett Indians. Roger Williams made Providence a haven for persecuted religious dissenters. He thought of Providence as a “lively experiment” in religious liberty and church-state separation. And so it became such.

The Founding of Warwick

Samuel Gorton, another person ordered to leave Massachusetts (in 1638) first went to Portsmouth, where William Coddington had started a town (see below). Gorton became disliked in Portsmouth so he moved to Providence. In both towns, Gorton created discord and was disliked by the community leaders because of his denial that any magistrate could control what he did. Finally, in 1643, Gorton purchased from the Indians a tract of land in what is now the town of Warwick, and settled there.

The Founding of Portsmouth and of Newport

Portsmouth, originally called Pocasset, was the result of William Coddington, who in 1637 was notified to leave Massachusetts. With the help of Williams, he settled on the site of Portsmouth, in the northerly part of the island of Rhode Island, which was then call Aquidneck. Subsequently Portsmouth became the home of Anne Hutchinson, when she was exiled from the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1638. She brought more settlers who were attracted to the colony by the promise of religious freedom. Disagreements between Hutchinson and Coddington arising at Portsmouth, Coddington, with a minority of his townsmen, in 1639 moved southward on the island and began the settlement of Newport.

From Settlements to Colony

In 1663 Williams secured a royal charter from Charles II, which provided for a colonial government for the Rhode Island and Providence Plantations. The charter not only separated Rhode Island from the Massachusetts colonies, but also brought Rhode Island and Providence Plantations together as one colony. After the charter from the King, Williams “nailed it down” by then securing the approval of the English Parliament and an offer of the charter to the four existing towns of Providence, Warwick, Portsmouth, and Newport. An assembly of delegates from the four towns accepted it

The charter provided for a General Assembly, with power to enact all laws necessary for the government of the colony, such laws being not repugnant to but agreeable as near as might be to the laws of England, “considering the nature and constitution of the place and people there”

The royal charter of 1643 was remarkable, because it was the first time a king in Europe departed from the then theory that the religion of the king should be the religion of the realm and its colonies. The charter ordained that no person should be in any way molested on account of religion! It is so important to the history of Rhode Island and to the United States that we quote a little of it below.

Charter of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, July 15, 1663

. . . And whereas, in theire humble addresse, they have ffreely declared, that it is much on their hearts (if they may be permitted), to hold forth a livlie experiment, that a most flourishing civill state may stand and best bee maintained, and that among our English subjects. with a full libertie in religious concernements; and that true pietye rightly grounded upon gospell principles, will give the best and greatest security to sovereignetye, and will lay in the hearts of men the strongest obligations to true loyaltye: Now know bee, that wee beinge willinge to encourage the hopefull undertakeinge of oure sayd lovall and loveinge subjects, and ….

….because some of the people and inhabitants of the same colonie cannot, in theire private opinions, conforms to the publique exercise of religion, according to the litturgy, formes and ceremonyes of the Church of England, or take or subscribe the oaths and articles made and established in that behalfe; and….

….by reason of the remote distances of those places, will (as wee hope) bee noe breach of the unitie and unifformitie established in this nation: Have therefore thought ffit, and doe hereby publish, graunt, ordeyne and declare, That our royall will and pleasure is, that noe person within the sayd colonye, at any tyme hereafter, shall bee any wise molested, punished, disquieted, or called in question, for any differences in opinione in matters of religion, and doe not actually disturb the civill peace of our sayd colony; but that all and everye person and persons may, from tyme to tyme, and at all tymes hereafter, freelye and fullye have and enjoye his and theire owne judgments and consciences, in matters of religious concernments, throughout the tract of lance hereafter mentioned; they behaving themselves peaceablie and quietlie, and not useing this libertie to lycentiousnesse and profanenesse, nor to the civill injurye or outward disturbeance of others; any lawe, statute, or clause, therein contayned, or to bee contayned, usage or custome of this realme, to the contrary hereof, in any wise, notwithstanding….

It was because of the governmental guarantee of religious freedom that thereafter the Providence Plantations and Rhode Island gave protection to Quakers in 1657 and to Jews from Holland in 1658.

The following map shows the three colonies of Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Rhode Island and the counties that were defined within them as of 1703. Notice how Rhode Island had only two counties, reflecting the separate nature of the “Providence” area of Williams and Gorton from the “Rhode Island” area of Anne Hutchinson and Coddington.

Early History of Providence and Rehoboth

Providence during its first forty years (1636 to 1676) was exclusively a fishing and farming village, laid out along “the Towne Street”, a dirt road which wound along the eastern shore of the Providence River. This road (present-day North and South Main streets between Olney and Wickenden streets) was the main artery of Providence for the duration of the colonial period and beyond.

The town was greatly destroyed during King Philip’s War. In the years following some commercial activity began, and new or farming families moved outward to the town’s remote lands bordering upon Connecticut to the west and Massachusetts to the north. Despite this growth, however, the entire population of Providence in 1708 was only 1,446. (1708 was the first colony-wide census taken by Rhode Island.).

By 1730 the population of Providence was 3,916, and so many farmers had moved into the “outlands” of Providence that three large towns were set off from the parent community in 1731 (Scituate, Glocester, and Smithfield). Before the colonial period came to a close, an inner ring of three more farm towns (Cranston, Johnston, and North Providence) were carved from Providence’s territory. The Providence city that remained was less than six square miles, with about 4000 persons, around the river and predominately commercial in character.

The present 21st century towns of East Providence and the present part of Pawtucket east of the river were then (1774) part of Rehoboth. Rehoboth in the 1700’s was part of Massachusetts, but Rehoboth and Pawtucket were economically and socially tied to Providence, not to the Massachusetts colony.

Providence “area” including Rehoboth at the start of the Revolution

By the middle of the 1760s– the eve of the Revolution– Rehoboth was roughly comparable to Providence. The Massachusetts census of 1763-65 shows that Rehoboth had 617 families and a population of 3,637. The Rhode Island census of 1774 shows Providence with 655 heads of families and a total of 3,950 persons.

By 1760 Providence had a flourishing maritime trade, a merchant aristocracy, a few important industries, a body of skilled artisans, a newspaper and printing press, a stagecoach line, and several impressive public buildings. For lack of a port comparable to Providence, Rehoboth lacked the maritime trade, but made up for it in its access to land available for settlement.

Rhode Island was part of the tremendous growth of New England. Between 1750 and 1770, the American colonies grew from 1 million to 2 million people and continued to double every 20 years. [Wood 1991, p. 125].

Shipbuilding was well established in New England before the Revolution, and in New England, Massachusetts was preeminent. A visiting Englishman reported back to London in 1769 that 389 vessels totaling 20,000 tons had been built in the colonies that year. Massachusetts accounted for 35 percent of the vessels, launching 137, with an average tonnage of 60. In 1774, one-third of the British merchant fleet was American-built; by 1775, the colonies were building 35,000 gross tons of shipping annually.

Rhode Island was not a factor in ship building, but it was in ship operation. Most of the Rhode Island free male population was in one way or another involved in ship operations or the merchant trade.

There were four Brown brothers who were prominent in the Providence area, because of their astute understanding of how to make money in this new economy. It is summed up well as follows.

In the economic realm, the famous Brown family of Providence rose to new financial, commercial, and industrial heights, surpassing in stature even the celebrated merchants Aaron Lopez, Joseph Wanton, and Christopher Champlin in Newport and James D’Wolf of Bristol. The resourceful Brown brothers — Nicholas (1729-91). Joseph(1733-85), John (1736-1803), and Moses (1738-1836)- guided by uncles Obadiah (1712-62) and Elisha (1717-1802), laid the groundwork in this turbulent age for the remarkable commercial and industrial advances of the early national period. http://www.rilin.state.ri.us

Revolutionary Providence: 1765-1790

England’s passage of the Sugar Act in 1764, levying a duty on sugar and molasses imports so essential to Providence distilleries and to the “triangular trade” in rum and slaves, set in motion a wave of local protest which crested in 1the 1770’s. As the colonies edged toward the brink of separation with England because of subsequent measures such as the Stamp Act, the Townshend Duties, the Tea Act, and the Coercive Acts, the town of Providence became a leader of the resistance movement. autonomy including the power to tax.

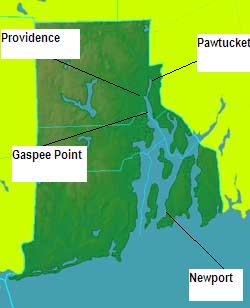

Rhode Island was a good place for a smuggler. The colony was only 1,200 square miles (about 50 miles long and 25 miles wide) but it had 384 miles of coastline, with many bays and coastal indentions fit for ships to land. The few ships of the English Navy in the colonies could not stop smuggling entirely. An English ship at Newport would only be able to ship entering one of the three entrances of Narragansett Bay and headed to the merchants at Providence.

Rhode Island was a good place for a smuggler. The colony was only 1,200 square miles (about 50 miles long and 25 miles wide) but it had 384 miles of coastline, with many bays and coastal indentions fit for ships to land. The few ships of the English Navy in the colonies could not stop smuggling entirely. An English ship at Newport would only be able to ship entering one of the three entrances of Narragansett Bay and headed to the merchants at Providence.

In June 1772 Providence merchants and sailors burnt the customs sloop Gaspee, and in June 1775 they burnt tea in Market Square. Providence citizens led the way in calling for the Continental Congress, in founding a Continental navy, and, on May 4, 1776, in renouncing allegiance to the king.

Providence in 1774 had 4,321 inhabitants, with 655 families residing in approximately 370 dwellings. A 1776 survey shows 726 Providence men capable of bearing arms. There were six distilleries, two spermaceti candle works, two tanneries, two gristmills, a slaughterhouse, a potash works, and a paper mill. Some two hundred tradesmen and artisans represented more than thirty-five different services and skills. Economic activity was dominated by three mercantile firms: Nicholas Brown and Company, Joseph and William Russell, and Clark and Nightingale.

Fortunately, Providence escaped enemy occupation, a fate that arrested Newport’s growth. In December 1776 a three-year occupation of Newport began, forcing many of that town’s inhabitants to take refuge in Providence–a reversal of the pattern in 1676 during King Philip’s War, and a reversal of the relative importance of Rhode Island’s two principal towns.

During the war American troops were quartered in Providence en route to various campaigns, though perhaps a thousand were permanently stationed here as a protective force. French troops moved in and out of Providence from July 1780 to May 1782, and it was from this point, in June 1781, that Rochambeau’s army began its fateful march southward to Yorktown.

Business enterprise in Providence was not destroyed during the Revolutionary War. During the three-year blockade of Narragansett Bay, Providence entrepreneurs imported their wares through the ports of New London and New Bedford.

From Town to City: After the Revolution

With war ended, Providence resumed its pattern of growth. Its citizens and entrepreneurs weathered a postwar depression (1784-86) and then scaled new economic heights. When American ships were barred from the British West Indies in 1784, local merchants replaced this important colonial trading partner with ports in Latin America and the Orient.

During the early years of the republic, Providence moved into the front rank of the nation’s municipalities, first as a bustling port and then as an industrial and financial center. Providence merchants, especially the Browns, experimented in manufacturing. Samuel Slater was their first important protégé. Slater’s mill equipment moved Rhode Island into not only cloth production, but also taught Rhode Island how water power could be used in manufacturing all sorts of items.

By 1830 manufacturing had replaced maritime activity as the dynamic element in the economy. Providence’s four major areas of manufacturing were base metals and machinery, cotton textiles, woolen textiles, and jewelry and silverware. Industry became become the principal outlet for venture capital and the primary source of wealth.