The following history of land ownership is helpful in understanding the early (pre 1670 or so) tensions between Massachusetts and those early inhabitants of the Rehoboth area, now a part of Rhode Island.

Students of the early (before 1700) history of the Pawtucket/Rehoboth area may seem puzzled by the seeming lack of care of the early settlers in the Pawtucket area to record their existence or seek legal purchases of land in the area. In fact, they were being prudent.

The “Warwick Patent” of the King, in 1630, through the Council for New England, in England, granted the entire territory of the Plymouth Colony to “William Bradford, his heirs, assigns, associates and assigns”, with all the formal legal words that made Bradford the absolute and sole owner. In other words he and those he chose were the owners of the land. The description of the land he was granted was vague, because of the lack of knowledge of the land. But whatever defect there may have been in describing the northerly boundary (and hence the line to be drawn between the Plymouth Colony and the later Massachusetts Bay Colony), it was reasonably clear that he and his associates were to own land westward from the Plymouth Colony, but not clear how far westward into or near Narragansett Bay.

Bradford immediately took in as his “associates” the previous earlier purchasers under a prior patent, and they could have continued to regard themselves as owning all the land. However, they regarded themselves as only being trustees for the community, except they reserved for themselves, as sole owners, three tracts of land running up to the east edge of Narragansett Bay and the north-south line of what later became known as the Pawtucket and Blackstone Rivers.

As new settlements were needed, by population pressure, outside of the original Plymouth settlement, Bradford would assign an appropriate portion of his titled lands to the new settlement. But the three tracts, to which he and his associates had kept the full legal title, were not in the assignments for new settlements in the Plymouth Colony.

In 1639 and 1640, the Massachusetts Bay Colony and the Plymouth colony tried to settle their differences about the dividing line between their lands. Among other things, they had a dispute about the land immediately to the east of the Narragansett Bay. As part of the settlement the commissioners asked Bradford to surrender his patent rights to the Plymouth Colony, so it in turn could settle its land disputes with the Bay Colony.

In March 1641, Bradford formally surrendered his patent rights to the “Body of Freemen” of the Plymouth Colony, but — again, consistently reserved the three previously reserved lands to his sole ownership. The third tract so reserved was described as:

“The third place, from Sowamsett River to Pawtucket River, with Cawsumsett Neck.. . . . extending into the land eight miles through the whole breadth thereof”

This reserved tract number three comprised the present Swansea, Rehoboth, Seekonk and Attleboro, MA, and East Providence, Cumberland and Pawtucket, RI. (Bradford 1650, pp 428 – 430 and Bowen, Early Rehoboth 50.]

Bradford was the Governor of the Plymouth Colony, so it is not surprising that his ownership would be protected by the colony, acting through its General Court. Governor Bradford and his son Major William were particularly interested in the tract number three. [Bradford 1650, p 430]. The west part of this tract was claimed by the Massachusetts Bay Colony, so settlers in the area who did not claim to have title from Bradford were a threat to Bradford’s land title. English law of the time would recognize his allowing settlers without title from him as either being an admission that he did not own the property claimed by the Bay Colony, or else a relinquishment of the by adverse possession of others, if the adverse possession lasted long enough.

After Bradford surrendered his patent, in 1641, the Massachusetts Bay Colony was recognized by the Plymouth Colony as having at least political and judicial control to a mile or two on the east side of the Pawtucket River. This included what would become the Pawtucket town on the east side of the River. Now, for the first time, it was at least “awkward” for Bradford to be able to throw settlers out of the land on the east side of the Pawtucket River and the Narragansett Bay.

Now, with that understanding, it is easier for us to understand some of the early history of the Rehoboth area, and why in about 1641 to 1644, there was a shift in how one obtained a right to say that one “owned” land in that Providence/Pawtucket/Rehoboth area. Let us follow the history further.

When Roger Williams came, in 1636, to what is now Rhode Island, he bought land from the Indians, who he recognized as owning this wild part of the country. Williams settled in the Rehoboth/Seekonk area, on the east shore of the Bay and the Pawtucket River. The Plymouth Colony claimed he was on their land, and had to leave. Williams was forced to move across the Bay and River to Providence. All who came after Williams and settled in the area met the same fate until 1641. That is, they attempted settlement by buying land from the Indians, the Plymouth Court (the general assembly), probably at the behest of Bradford, took issue and forced the removal of the settlers.

Shortly before Bradford’s surrender of patent rights, noted above, the Rev. Newman asked for permission to settle in this area. Newman was somewhat of a thorn in the side of the Plymouth Colony, because although not an out and out dissenter, his views were somewhat different than the established church, and he was strong minded, intelligent, and vigorous in leadership of his flock. In 1641, Newman purchased the right to settle, and received permission to settle in the area, from the Plymouth Colony. He named the settlement Rehoboth.

With the 1641 Newman purchase, and the settlement of the boundary dispute with the Bay Colony, Bradford seemed to lose interest in protecting title to the land immediately north of the Newman settlement and within the land now in the Bay’s legal jurisdiction.

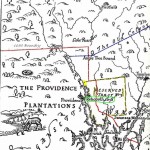

The map on the left (click to enlarge) shows how Bradford understood his reserved tract number three to be in 1650. The yellow spot is what the Plymouth Court would have understood, from descriptions, if persons were reporting where Hazels (see discussion below) was located. The red line is the west boundary of the Plymouth Colony after the settlement of 1641. The place labeled as “Rehoboth 1638” near the left bottom corner of the tract three is a reference to the place Williams originally settled. (The Rehoboth of Newman’s 1641 settlement was further north of the settlement of Williams, although communications and mapping being what they were in 1641, that may not have been understood back in Plymouth.) When Williams was thrown out of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, he went to the specially reserved tract No. 3 of Governor Bradford of the Plymouth Colony! No wonder that Williams had to move from “his” Rehoboth to found Providence across the river/bay!

The map on the left (click to enlarge) shows how Bradford understood his reserved tract number three to be in 1650. The yellow spot is what the Plymouth Court would have understood, from descriptions, if persons were reporting where Hazels (see discussion below) was located. The red line is the west boundary of the Plymouth Colony after the settlement of 1641. The place labeled as “Rehoboth 1638” near the left bottom corner of the tract three is a reference to the place Williams originally settled. (The Rehoboth of Newman’s 1641 settlement was further north of the settlement of Williams, although communications and mapping being what they were in 1641, that may not have been understood back in Plymouth.) When Williams was thrown out of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, he went to the specially reserved tract No. 3 of Governor Bradford of the Plymouth Colony! No wonder that Williams had to move from “his” Rehoboth to found Providence across the river/bay!

When Newman arrived, he found John Hazels living nearby, north of the Rehoboth settlement, and claiming 600 acres as purchased from the prior owner who had been forced to leave by the Plymouth Court, as not having good title and they wanted him “out”. There were a number of practical reasons for Newman recognizing Hazel as a part of the Rehoboth settlement, even though Hazels did not have his title through the Plymouth Court. Newman treated Hazels as a sort of good neighbor participating in the events of the settlement proper.

Hazels must have sold or given some sort of right to William Bucklin to have a house on his land, for the Rehoboth Town Meeting Records of 1 Feb 1645 state:

“…At the same time the way to William Buckland’s house is agreed on by those partyes which it doth conform.”

This notation was unusual, because the Newman congregation had organized as a proprietary body, all the townspersons with Newman had definite allotments from the purchase which Newman’s congregation had jointly made, and there is no record of Bucklin purchasing anything other than the Hazel land, as noted below. Because Hazel’s land was outside the Rehoboth title purchase, only Hazel and Bucklin could seem to be involved in “agreeing” on the easement to get to Bucklins house. The notation suggests two things:

- that Bucklin was inside the Hazel 600 acres by 1645, not even wanting to be an owner of record, probably because of the problems that would arise if the Plymouth Court knew of the existence of people living in the area outside the land granted the Plymouth to Newman (especially if the “outsiders” were non-conformists); but

- that the Rehoboth Town Meeting was being used by Bucklin as a friendly local adjudicator to see that Bucklin had access to his house and would have some standing if Hazel were to change his mind later.

(As an aside, Bucklin may have had unpleasant reasons in 1645 for leaving Hingham, where he owned substantial property and had been living since 1634, and seeking a move to a more friendly neighbors. In 1645 the town of Hingham was in deep and unseemly divisions, neighbor against neighbor, with some men being jailed for disobedience in regard to who were to be the officers of the town militia, and the town seeking the impeachment of Governor Winthrop. And, perhaps more importantly, see the notes at the end of this page, which refer to a religious reason why events leading up to 1645 may have pushed William westward toward Williams.)

In 1649, the Plymouth Court (the general assembly) heard a complaint about Hazel settling in the area, but confirmed in Hazels the right to be there on a tract of 600 acres abutting the land previously granted to Newman. (Indeed, if the Plymouth Court had sought to throw him out, it could have raised a problem with the previous settlement with the Bay Colony, which gave the Bay Colony legal and political control of that exact spot. Still Hazels seemed to be uneasy in being in the jurisdiction of something other than Rhode Island. He decided to move across the river to Rhode Island. He sold his 600 acres to Edward Smith, who was the town clerk of Rehoboth, who immediately in turn sold it to William Bucklin.

Volume 1 of the old Proprietary Records of Rehoboth, in a 1651 entry, shows Bucklin entering a description of the land as being his (to wit: the description recorded of his land Bucklin fits fairly precisely with the bounds of the 600 acres of land described in the 1649 Plymouth Colony records as being the land confirmed to Hazel) and saying he purchased it from Smith. The use of Smith, who happened to be the town clerk, as the founding link of Bucklin’s land title, gave Bucklin the appearance of having title from the Newman Colony, which title the Bay and Plymouth colonies would respect if they did not inquire too much.

Read more about Bucklin’s 600 acres.

William Bucklin’s wife’s parents were Quakers, and William himself never joined the established churches, not even that of Rev. Newman. The early Bucklins were staunch Baptists, so probably William himself was of the Baptist persuasion. (Note, e.g., son Benjamin born in Hingham was christened after his 1640 birth, not baptized, which would have marked William and his wife as being Baptists.)

In about 1641, both the Bay Colony and the Plymouth Colony became more concerned about “wickedness” and “offenses against churches.” Persons who were not outspoken enough to be banished, like Williams had been, were still fearful of being punished for unorthodox behavior. In particular, the Bay Colony was unfavorably impressed with the “Islanders” in the colonies set up by Williams, Hutchinson at Portsmouth, Coddington at Newport, and Groton at Warwick, and debated whether to annex Rhode Island by force, or persuade Plymouth to do it, or leave them alone. Read what the Bay Governor had to say about these Islanders in 1642:

“[C]oncerning the Inlanders…Neither is it only in faction that they are divided from us, but in very deed the rend themselves from all the true churches of Christ . . . by some of their under workers or emissaries who have lately come amongst us and have made public defiance agasint magistracy, ministry, churches and church covenants, etc. as antichristian. Secretly, also, sowing the seeds of Familism and Anabaptistry, to the infection of some and danger of others.” [March 1642 letter reprinted at 318 Bradford 1650].

Before the Bay Colony could reach a decision in their debates, Williams obtained the Providence Plantations Patent from Parliament in 1644, giving unassailable legal standing to protect those settlements as a separate land patent. This was fortunate, since by the end of the 17th century, Rev. Cotton Mather, the best known of the Massachusetts ministers, called Rhode Island “the cesspool of New England”. With the protection of the1644 Patent, Williams and other religious non-conformists might well have been swept out of the lands to which they had fled. With the 1644 Patent of Williams, religious non-conformists were much more in ease of mind if they were closer to William’s Providence than to Boston or Plymouth.